Photo from konaworld.com.

There’s something of an adoration–occasionally bordering on idolatry–for the working men and women of professional bike racing. We hold high racers such as Erik Tonkin, Tristan Schouten, and Mo Bruno-Roy who put in a full week’s work and still make it to the podium on the weekends. That esteem is, in part, a recognition of their serious dedication to the sports we love and their willingness to sacrifice time to compete at the highest levels. But it is also that we can see ourselves in working pros, unrealistic as that is. Few of us will actually spend the time training to compete at that level and even fewer have the genetics to do so. But their success feels just a little more within our grasp, a little more aspirational to those of us finding time to train and race in between all of life’s other commitments.

And though he eschews the notion that his full time job is a badge of honor or an excuse, Spencer Paxson falls squarely among that top tier of American working pros. He routinely places in the top 10 at national-level professional cross-country mountain bike races, placed 5th at the 2012 cross-country nationals, has made the US World Championships selection, and was on the 2012 Olympics long team. I spoke to Paxson about the challenges of balancing his office job with his bike racing job, what it means to have a career as a cross country racer in the ever evolving world of mountain bike racing, coming up under the mentorship of Erik Tonkin, and much more.

What is your day job?

I work for Atlantic Power Corporation. It’s an energy infrastructure company. I’m in the renewable energy development division developing wind energy and solar energy facilities.

How do you balance full time work with the demands of training as a professional bike racer? What sacrifices do you have to make on either end?

By way of background, I’ve been with the company for six years now. It’s actually what brought me out to Seattle after I finished school. Over the years, one of the biggest things I’ve negotiated is time and flexibility as opposed to defined positions and salary. The work is fun, I enjoy it a lot. I do the work and negotiate the things I value more, which is always time. It’s let me create a schedule where I can fit in training and travel and all that.

I live in Bellingham and work from home now. Every year my responsibility grows which makes the balance a little bit harder. But I have a lot of autonomy and flexibility. I work at a computer all day, email or phone conferences. Most of the people I work with are actually on the east coast so my days start early and end early. I can fit in time for training after work. I think if I was a road racer it probably wouldn’t work. But I’ve been figuring out every year how to train as efficiently as I can. I’ve discovered with mountain biking the volume is totally manageable with a 40-50 hour work week. Especially since I can structure that work week to my benefit without sacrificing either one.

It’s such a fortunate situation. I can’t say it will last forever, but for time being it works.

Do you feel like you’re able to get a training volume comparable to that of a full-time bike racer?

I think so. Everybody’s different. Some people need way more volume. Others need less. But the truest test is performance at races itself. Over the last couple of years I’ve gotten the results. I’ve been getting better every year. I’m competing with guys who maybe don’t have the same types of non-cycling obligations I do. But I don’t have kids. There are those racers with kids. It’s a bigger deal for women racers, obviously, but even for the guys it’s a big commitment.

I’m definitely not unique in the fact that I have a job and race a bike. I think that’s probably 98 percent of everyone who races a bike. For me, I don’t like to use the word luck because it discounts the decisions I’ve made that led to my current situation. But I have a fortunate set up with the company I work for and the sponsors I have and the engine I’ve been able to build for myself as a bike rider. All of that together creates a level of achievement that’s so motivating for me to continue.

I feel like there’s this thing where having a non-cycling day job and racing the elite ranks is either a badge of honor or an excuse. I don’t really like to distinguish either one. In my mind they go together. I think it’s the same for so many different racers. Whether they have a full time job outside of cycling or they have more obligations with sponsors and contracts and families outside of racing. I think it’s truer in mountain biking than other disciplines of racing.

In mountain biking, you are a living billboard. If you’re riding for a big factory team, you’re usually riding for a bike company. You are directly influencing that product. Your sponsor’s return on investment is your portrayal of their product and their message. I think that’s pretty unique to the sport of mountain biking because it’s so small. There are teams out there that are a combination of brands and shops and outside industry companies. But for the most part it’s Specialized, Giant, Trek, and, though they’re smaller, Kona.

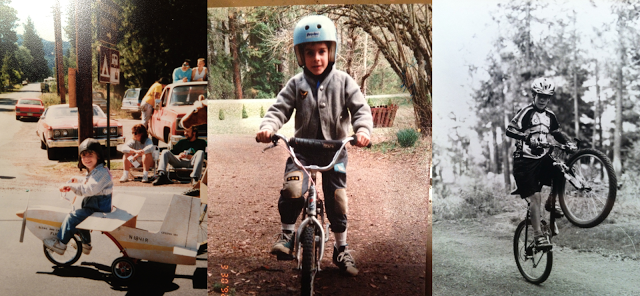

The earliest days. Photos via Spencer’s blog.

What sort of role do you play as one of Kona’s top racers? Do you do a lot of product feedback, demos and shop visits, etc?

Kona is an interesting team. We cover the whole spectrum of dirt from Graham Agassiz all the way to Helen Wyman. We’ve got Barry Wicks, Antoine Bizet. Then there are guys like me. I’ve had a lot of success lately, but I’m not an icon at all. I think the days of becoming an icon like those names is a lot different now. But anyway, that aside, Kona is all about the people. It’s a small company. The XC guys are me and Barry, Kris Sneddon, Cory Wallace. Most of the time we’ll travel together. When we were racing Bonelli and Fontana we stayed down in California the week between. I was able to work remotely in the mornings. In the afternoons and evenings we’d lined up shop visits and rides with as many of the Kona dealers as we could fit in. We’ve done that with a lot of our domestic trips. We’ll go travel and do the race. But we’ll also work with the local sales rep and do meet and greats and that type of thing. It’s really cool.

I live in Bellingham, which means I’m lucky enough to be really close to Kona headquarters. That was just circumstance how that played out. I’m able to work with the guys doing product development. I’m not an engineer. But I can pitch in on the qualitative ideas of the bike. It’s been really fun feeling like I’m contributing something beyond results themselves.

Also, Kona’s big on promotional videos. I’ve been on several totally awesome trips up in Canada and Hawaii, filming with helicopters and riding great trails. It’s a cool scene at Kona. It’s a lifestyle company, but it’s performance as well. As a rider it’s a total blast. It adds this whole other level of value for me beyond the races.

You mentioned becoming an icon in racing now is different than it used to be. Is a lot of that related to the discipline you choose? Your focus has largely been XC and short-track XC racing the past few years. Is there momentum pushing you towards enduro or other gravity-focused events?

I think about that all the time. The theoretical path towards becoming a top name in the sport–and if that’s your main goal, maybe you should question your motives–is to have great results in racing. If you’re successful in XC these days, it doesn’t necessarily do that. The sport of mountain biking is so diluted now. I guess that’s kind of a negative word. From a negative point of view it’s diluted. From a positive point, it’s diverse. And that makes it hard. But looking at it as a whole it’s great.

There are more people than ever doing some discipline of the sport. How many new kids are showing up on Pink Bike doing insane tricks and making really cool videos? How many more high school kids are doing the high school mountain bike leagues or doing youth development league racing? There’s so much there. But to break through and become an icon in the way you or I might think of is harder. Not to discredit anything they did, but those icons came up in a time when the path was simpler and more defined. You were either a XC racer or a downhiller and that was it. You were either on a track towards world cup racing or dominant nationally. Now it’s all over the map. It’s a good thing for the industry as a whole. But for the individual racer there are a lot of pegs to fit yourself into.

Do you think there’s still a career to be had as a XC racer? And if that’s your goal is it all about focusing on the world cups?

It’s definitely not all about the world cup and I don’t think it’s been that way for a while. But to answer your question, yes there’s definitely a career path in XC mountain biking. I don’t think it’s gotten any easier to make it a sustainable career in the classic sense of the world. If it all boils down to how you’re compensated value for value, at the end of the day it’s probably harder now. But that said, there are so many ways you can create value today. Maybe the ironic thing is it’s less about results and more about the value you add through the story and being part of a company that values your promotion of their product. Unless you can go to the world cup and get top 5 or top 10, it doesn’t resonate with anybody who’s in the business of selling mountain bikes, save for the few people who know what it means to finish even in the top 50 in a world cup.

The opportunity is there. It leans heavily on relationships, which is nothing new. But in terms of the money that’s available in it to make it your only career, I think it’s probably pretty difficult.

How did you get into bike racing in the first place?

I grew up in Trout Lake, Washington. It’s a little cow town in southern Washington in Klickitat County. It’s in the Columbia River Gorge area near the border with Oregon. I pretty much stumbled on mountain biking by accident. I rode my bike around to hang out with my buddies as a kid. We found these cow trails behind our houses one summer when we were 12. We would tear around on the trails on our janky CostCo bikes.

Later that summer, I was in the checkout stand at Safeway and saw a copy of Mountain Bike magazine. I picked that up and was like whoa, this is a legit sport! There was an advertisement for the Timberland Gorge Games mountain bike race at Post Canyon, which is still a big trail network in Hood River, Oregon. I signed up for the junior sport category and got my ass kicked. But I had such an awesome time.

After that I started racing the local Ski Bowl series up on Mount Hood the rest of that summer. I saved up a bunch of money and bought a Gary Fisher mountain bike. Pretty much from there on I kept racing. My folks got into it too. They were pretty young. They were in their late 30s, early 40s. We would go to races together, the OBRA (Oregon Bicycle Racing Association) series. I started having a little more success and got a little more serious.

I interviewed Barry Wicks a while ago and he talked about getting his start racing in the Ski Bowl series. Is that where you first came across him?

Barry and I share a very similar upbringing. I met him racing the OBRA series. He’s three or four years older than me. He was already this precocious, insanely fast, talented kid. I didn’t really know him personally until I started racing for Kona in 2011. But the biggest connection he and I have is our sort of unofficial mentorship with Erik Tonkin during our young racing years. Tonkin had taken Barry under his wing in the early 2000s. He took me under his wing when I was 18 or 19. I give him a lot of credit for planting most of that baseline philosophy on the workman approach to professional cycling.

Leading the Le Mans start at the 24 Hours of Old Pueblo. Photo via Pinkbike.

What was your path from being Tonkin’s mentee to your pro career?

I was working at Discover Bicycles in Hood River and rode for their shop team. Then during college I made it onto the last alumnus of the Balance Park DEVO teams under John Kemp. The whole team is kind of a legacy in and of itself. I don’t know if I belong on the roster of the other people who have come through that team. That got me through college. I went to Middlebury College out in Vermont and only raced in the summer months. But I had enough success that Erik continued to notice me any time I was racing in Oregon. Once I graduated out of the U23 ranks, Erik was really interested in having me race for Team S&M, the Sellwood Cycles team. He helped get me to a lot of bigger ProXC races. He made sure I was getting to the right races and doing well.

In 2010 I had my first real breakout ride at Nationals in Colorado. I got 7th place. It was a bit of a Cinderella story. For most people I was just this kid riding in the shop jersey on a big heavy bike and I wasn’t too far off the podium that day. I made the elite Worlds team that year. Things really shifted after that. The next year I signed with Kona as a factory team member, but not a paid professional position. And that’s pretty much the full track to today.

Now that you’ve been racing as a professional for a couple of years, what are your goals both near term and long term?

That’s a big question. I’ve been racing since 1998 and in 2008 I got really serious. That was post college and it was a more weighty decision than in years prior. My number one goal–it sounds super cheesy–has been to make this a sustainable thing that I can do because I love the sense of purpose it gives me. Whether or not I’m pursuing the Olympics, which has been a longterm goal of mine since childhood that I haven’t given up on yet. That’s the longest term goal in racing. It’s been about carving out this lifestyle where I’m not hamstrung by the financial limitations that the bike world presents and still having fun with bike racing. If it means I can continue on this track towards the Olympics or another couple of years trying to get podiums out of national-level events, I still get a lot out of that.

But I’m also 29 at this point. My long-sided view on racing is that I don’t necessarily see myself doing it the way I’m doing it today four years from now. I’d love for it to be something else, so I’m laying the groundwork for that. It’s a constantly shifting thing.

If you’d asked me five years ago what my goals were they would’ve all been very concrete. I wanted to get top 10 at nationals. I wanted to go race the world cups and see what it’s like to race in Europe. I wanted to try and get on a pro team. I’ve achieved so many of the goals I’ve set out in front of myself. The last distinct goal is I’d love to make it to the Olympics. But it’s really hard. Only one or two people can go. Any given year there are at least five to seven people who can make the cut. I was on the Olympic long team in 2012 and learned a lot from that experience. I’d like to go again.

What happens after that four year mark when you’re doing things differently?

I’ve got a pretty long-sided view on this Bellingham gig I’ve got. My girlfriend and I live here. I envision us staying the Pacific Northwest, if not Bellingham, for a while. I’d love to stay involved with Kona in some capacity, even if it’s not as a racer. Maybe a brand ambassador so I can contribute in some real way. I think Joe Schwartz is a cool example. He used to ride for Kona on the Klump team, he was one of the early freeride shredders. He was in all the New World Disorder movies. He does his own thing now, but he’s still very much involved writing cool pieces for Kona and carrying his achievements from his heyday and parlaying that into pretty cool adventure gigs nowadays.

Like what you read on The Bicycle Story? Support the work with a donation or by buying a shirt.