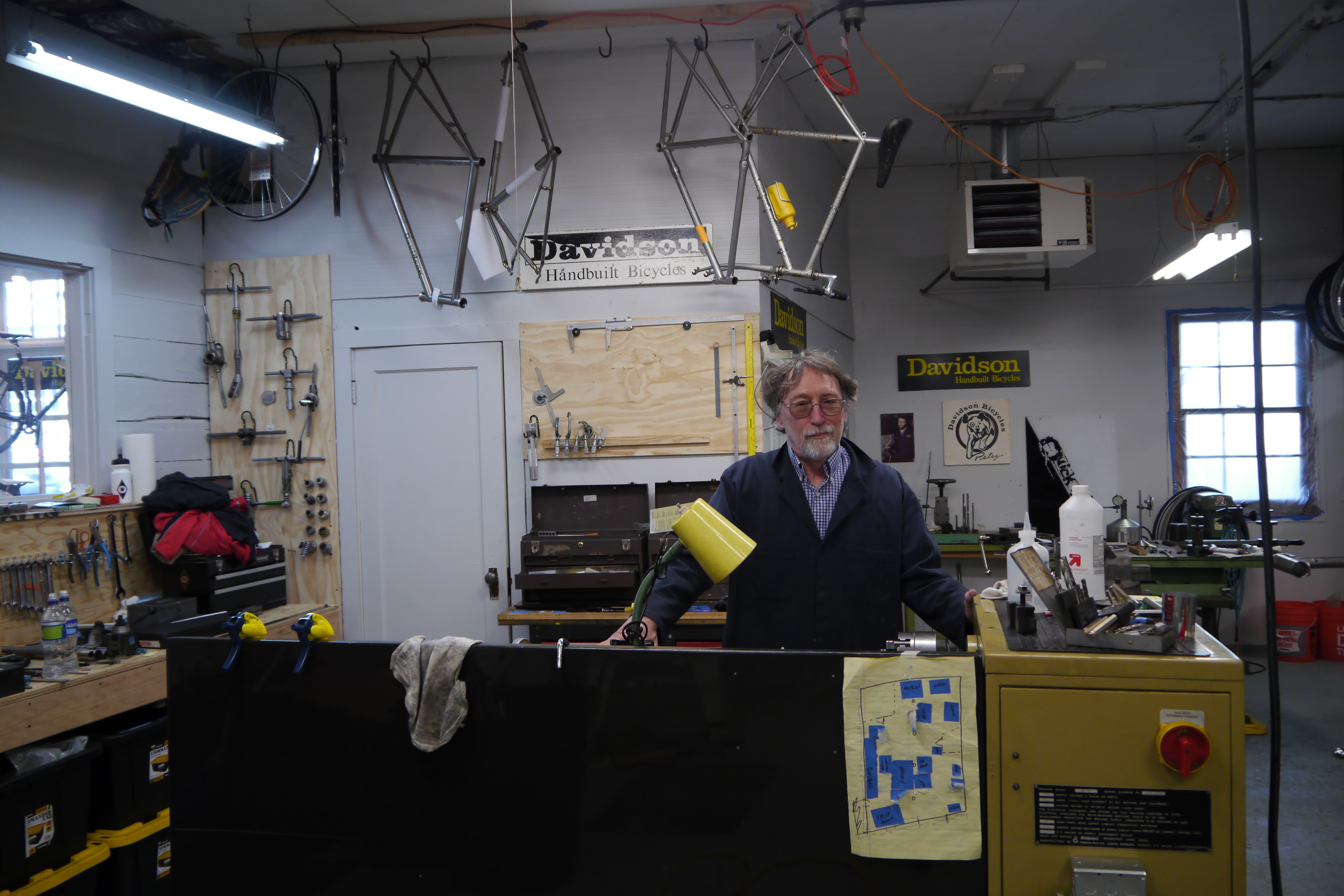

Bill Davidson in the new Davidson-Kullaway shop. Photo by Josh Cohen.

A few months ago, custom bike builders Bill Davidson of Davidson Bicycles and Max Kullaway of 333 Fabrication officially joined forces after many years of quiet partnership. One of the cool features of the new Davidson-Kullaway custom frame shop in Seattle’s Fremont neighborhood is a picture window in the wall that separates the customer area up front from the workshop in the back. It allows customers to watch the pair at work building beautiful bikes. When I arrived at the shop last week, I did just that. Kullaway was behind a translucent screen welding up a frame. Davidson, looking like a blue collar scientist in his denim shop smock, was standing over a milling machine cutting tubes. Eventually, they noticed me standing there and Davidson joined me up front.

If you know anything about frame building, Davidson likely needs little introduction. He’s been in the business for over 40 years, which puts him in the company of just a handful of other American builders. When he got started in 1973 there barely was such a thing as a custom frame builder in the U.S. We sat down at his new shop to talk about his long career, learning to build bikes in the 70s, the evolution of the frame building business, his new venture with Kullaway, and more.

How did you learn how to build bikes? There weren’t exactly UBI classes to take in the early 70s.

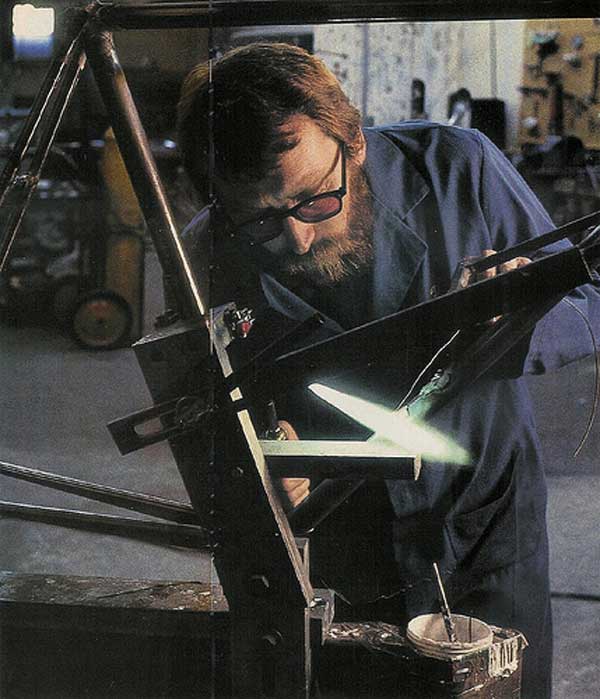

Interesting that you know that. A lot of people don’t know how difficult it was back then. Nobody here knew anything to show you. We Americans that started doing this back the are pretty much self taught or got a very, very brief education. Mine was extremely brief. I did have the advantage of having a dad who had a welding shop in Ballard, a neighborhood here in Seattle. I had some metal working experience to fall back on. But that didn’t mean that I wouldn’t make all the rookie frame builder mistakes back then. Again, no schools, no youtube, no magazine articles, no books. You just had to figure this all out yourself. Hopefully you would be a quick study and not make too many crazy mistakes along the way.

I spent a little time at a small shop in Liverpool, England called Harry Quinn Cycles. I suppose essentially I got one of those two week frame building classes. But they had no intention of teaching me. They just wanted to have me help them out doing grunt work and so forth while I was there. Some people called that an apprenticeship, but that was their words, not mine. I know how an electrician or a plumber or sheet metal apprenticeship works. My experience would not qualify as one. They were very friendly and interested in teaching me anything I asked, but they had to put money in the bank every week. No time to be teaching people that weren’t pulling their weight.

It’s interesting that you went to England. I know other early American builders such as Richard Sachs and Peter Weigle went to Whitcomb Cycles in England to learn as well.

Sure. How could you learn if the guy spoke Italian? There had to be some way you could ask question and they could understand it and be willing to answer. And that you would know when to stop asking questions and get out of their way. My trip was not planned to learn the craft. It just accidentally happened.

Why did you want to build bikes?

I was the typical young college boy who says, “I can do this. I’m a smart person with a little talent, of course I can.” I don’t think I was any different than the type of kid I see all the time now. What did they name it way back when? Yankee Ingenuity. I hoped I had a little to see me through. I think that was pretty much it. It was about the fun of being able to do it.

Bill Davidson in the early days. Photo via davidsonbicycles.com

You were already into cycling at that point, I assume.

Already a bike racer at the time. I was reading every single thing about cycling that I could get my hands on. It was all these foreign magazines that you could find. Italian ones and French ones and English ones of course. And the American Bicycling Magazine was just starting. The French were fun because their magazines had these little line drawings supposedly of the design of professional bike racers’ bikes. You could look at those and say, “so and so has a 72 degree seat angle” and “oh it looks like his toe is going to hit the front wheel,” etc. And of course everybody wanted to see the bike Eddy Merckx was riding. Or his challenger Luis Ocaña. We thought that’s what we should be racing on.

I suppose we bike riders have always been searching for just the right equipment to do our best with. The concept has seriously been taken up by the triathlete. “It must be something on the bike that makes you go fast!” or “even though I’m training, if I just have the right bike I’ll be way faster” kind of thing. Of course the roadies realized you have to be gifted by nature and train really hard. I suppose the two sports have somewhat evolved to be closer and closer together as far as the speed machines go. I think it’s the culture of Americans to think if I just got the right golf club I’ll be a better golfer. We’re the ones who drive bicycle technology really. The Euros take our ideas and sometimes perfect or adopt it and do well with it. But it’s pretty much mostly American ideas if you ask me. About gearing and aerodynamic rims and wider tires. We’re not so tied to convention as they are, I think.

What was it like getting one of Seattle’s first custom bike shops off the ground?

Back in the 70s and 80s we all looked at Colnagos and Masis and thought we just need to do a little better than that and we’ll have a good customer base. I was involved in the bike racing a little more than [the other frame building shop in town] R&E cycles was. Although Glenn Erickson eventually became quite involved in bike racing as well. I suppose back in the early days most of the bike racers asked me to make them their bikes if they were going to ask someone local. At that point only Glenn’s partner Angel Rodriguez was making the frames and he was more touring oriented. He loved the Alex Singer bikes long before they became re-popularized here in Seattle. He had one himself in 1973 or something. He liked those bikes and he wanted to emulate that and make the tandems and so forth. That was their first foray into custom bikes.

I’d already slightly cornered the market for local race bike production. We had really good riders in Seattle that were winning national championships and riding on European teams and cruising the country winning races and so forth. Of course I always knew it was them, the athlete, that was responsible. Like I said, there’s those other people who think it’s the equipment. I suppose I was the lucky benefactor of people thinking, “if I get one of those bikes I’ll be faster too.”

That seems like the reason any bike company sponsors a racer. “If you buy this $10,000 Specialized you too can race like Mark Cavendish.”

Of course it’s true. It was true back then too. There’s a psychology to it. I made bikes for one of Seattle’s most successful roadies, Mark Pringle. At first they were made of Reynolds 531, but then he asked me to make one out of Columbus tubing. Since he was up and coming, that Columbus tubing bike arrived just at the time he was doing his best. I think to this day he somewhat attributes those really successful years to that bike and what it was made out of. That bike just came into his possession when he was going to win 25-30 races a year, which he did for a year or two. That sort of thing helped push a lot of guys my way who might’ve been thinking about buying an English Raleigh or a Holdsworth or an Italian bike of some sort.

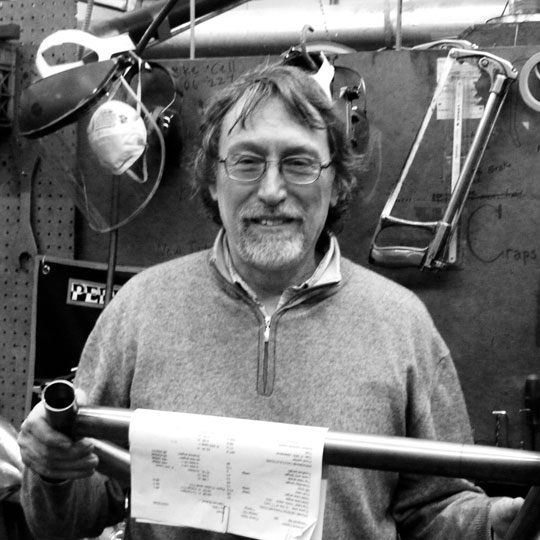

Other than there just being exponentially more builders out there than when you started, how do you think the custom bike world has evolved or changed over time?

Thirty five years ago, I knew all the builders by name and their work. We all sort of knew each other somehow. I couldn’t possibly know everyone now. Those frame building classes turn out that many a week. Frankly unless someone is outstanding they just don’t make it onto my radar. And you might have to be outstanding for some period of time.

It’s easy to make a great frame if you’ve taken five times longer than everyone else. Your girlfriend better have a good job because you’re certainly not going to contribute to the family income that way. I better be careful, I’m going to get a little outspoken here. There’s a couple guys making good looking titanium on the east coast that I’ve noticed lately. There’s a couple people making really great steel bikes on the west coast I’ve noticed.

Guys who’ve been at it as long as I have could double up their time on each frame and make it truly a work of art. But that’s the big question, right? Is it truly a work of art or is it a product that the buyer will be enamored with and the builder would’ve made a fair living from? I’m not at all impressed with the fly-by-night people who come out for three or four years then quits.

Bill Davidson. Photo via rapha.cc.

This might be a slightly ridiculous question given the number of bikes you’ve built over the years, but are there any bikes you’ve built that stand out as particularly special in your memory?

No. People come and bring things in once in a while that I’d totally forgotten about and I look at that and think, boy pretty good. Again, these are not works of art for me. I don’t finish it and stand back and say, my how pleasing this is. I’m more of the mindset that, did we satisfy this particular individual with this bike? And how are we going to do on the next one?

You don’t feel sentimental about them as they go out the door?

Not a speck. Remember, when I started making these it was for my fellow bike racer. He didn’t care that much about his bike as much as how did he do on that bike. If he did well then that became a great bike for him and I became a good frame builder for him. Our bikes have always been more like a ski racer’s pair of skis. Did he do his best race on those skis? If he did then they were great skis. If not, they weren’t. That’s basically my beginnings as a frame builder.

Sure they might’ve wanted chrome chainstays and have it painted metallic bright blue. OK, great. That was probably about the extent of the aesthetics then. And that being the case I just learned not to overly fuss. That’s why I’ve been able to keep doing it all this time. We’re great to the customer and good to ourselves and that’s how I feel about it.

Tell me about the new Davidson-Kullaway shop. Are you combining efforts?

Yes. We’re combining efforts. We each have something that we can do that helps the other. Right now I spend most of my time designing and manufacturing and fabricating for both of our brands. Although Max works with his customers. We’ve enjoyed working together in the past and felt that we could continue in a partnership business in that way. I’m a bit older, so I don’t think I’ll be able to do it as long as he will. That’s kind of how I look at it. It’s pretty hard to do this kind of thing by yourself. Max might finish welding up a frame and I can take it over and machine it and align it and finish it and decal it and have it ready for assembly while he does something else.

He currently has the best welding skill in this shop and, in my opinion, in the country. I look at all that titanium welding in the magazines and Internet articles and I say to myself–eh, I might even say it out loud–not on Max’s level. There are people out there who don’t know Max and are revering other people. Not on Max’s level. They may never be. It’s partly a gift. It’s training, but it’s partly a gift. You could train 18 hours a day on the best piano made, but you might not be the best piano player after that. The ones that are got a gift. Lots of people have a gift. Sometimes they find a way to utilize it. Sometimes it never surfaces. It’s lucky that Max found a way to utilize his gift, which is this really fabulous welding.

You started touching on this. After over 40 years in the business, is there anything left you want to accomplish with your career? How do you want to wrap up your time as a builder?

Well I don’t ever want to wrap it up. I can’t think of a better thing to do with myself.

[A Davidson customer Kevin who’s in the shop picking up his new bike chimes in. “Ask him about building bikes for folks with disabilities.”]

Kevin can really use the electronic shifting and powerful hydraulic braking system. And he doesn’t particularly want to have to clip in to pedals that require quick agility to remove yourself from. I like to be able to listen to the customer. I like to be able to help. You don’t have to be the national champion to get my interest. I feel like I can understand and work with anybody that needs something special. I even made an electronic shifting Dura Ace titanium tricycle last fall. This was for a person who wanted to race tricycles and try for the Special Olympics. He lives in the Bay Area and couldn’t get anyone to take his project on. I thought shoot, I’ll do this and I’ll enjoy it.

People have given me a lot of nice opportunities and I’ve taken as many of them as I could. I like that about this bike business. One of my colleagues in Seattle business, George Gibbs, ran his bike shop into his early-80s. He rode his bike to work every day until he couldn’t. If I’m lucky enough I’ll be like him.

Like what you read on The Bicycle Story? Support the work with a donation, by buying a shirt, or sharing it with your friends.

Pingback: The Bicycle Story: Bill Davidson on making bike frames in Seattle since the 70s | Seattle Bike Blog